“WE can walk along a path with no light, but how can we walk along a path with no dreams ….”

A character in Girish Karnad’s play says this. As the master creator bids goodbye to this world, his powerful words continue to resound! Certainly, dreams are central to our lives, our existence. That is why, in the dark times that we live in, dreams and the capacity to dream are being crushed with iron fists. There is every attempt to stifle voices, stifle lives and ultimately, stifle dreams. In this hour of terror, when public intellectuals, literary and cultural personalities had to make a choice – some shrunk into silence, some conveniently crossed over to the rightist camp and some risked their life to keep the torch of resistance burning. And Karnad belonged to the latter. He firmly stood by liberal, socialist and secular ideals in real life as in his creative works.

In his youth, when he was the Director of FTII, he resigned as Indira Gandhi declared emergency. His co-actor in the landmark film Samskara and co-founder of Madras Players, an amateur theatre, in which Karnad engaged during his Oxford University Press days at Chennai, Snehalatha Reddy, became one of the first martyrs of emergency in the country. Released on parole in critical condition after severe torture and solitary confinement in inhuman conditions in the Central jail of Bangalore, she died in five days.

Unlike Snehalatha or U R Ananthamurthy, who were initiated into social movements, Karnad was not, but he grew up under the influence of great thinkers and writers - D R Bendre, V K Gokak, A K Ramanujan, who had great concern for humanity. As a child, he grew up watching the theatrical prodigy and singer Balgandharva, who left a major influence on the music and theatre-scapes of North Karnataka, and later, the rich folk performances at Sirsi, a hill station in North Canara, where his father was posted on duty. During his graduate studies at Karnatak college, Dharwad, he came under the spell of eminent poet D R Bendre, and was encouraged by Manohar Granthamala’s G B Joshi and Kirthinath Kurtakoti. Karnad who aspired to become an English poet, conceived his first play Yayati, in which the father Yayati transfers the curse of old age to his son Puru for a life of sensual pleasures. The play’s anti-oedipal trajectory evoked a lot of interest in theatre circles. As a playwright, Karnad grappled with the ambiguities and absurdities in life and examined power, politics and sexuality through characters faced with strangest choices. In Hayavadana, where Padmini awakens to her desire for two men - her husband Devadatta and his friend Kapila, she is left with their transposed heads to choose from. Karnad’s distinctness is in his exploration of the human conflicts and complexities through transfiguring the myth, history and folktale. In Nagamandala, a play based on South Canara’s folktale, Karnad, highlights the plight of a neglected young bride Rani, whose husband Appanna is in an adulterous relationship. The situation is reversed on Appanna through the snake character that takes Appanna’s form and has amorous relationship with Rani, who believes it to be her husband. The play not only brings forth the double standards of the patriarchal society that doesn’t question Appanna’s adultery and demands innocent Rani to prove her fidelity, but points at reform through Appanna’s acceptance of Rani and the child she is pregnant with. In Tughlaq, a play that brought great recognition to Karnad, he sympathetically deals with the genuine political aspirations of an idealist Sultan and its devastation. Karnad directed only one of his own plays – Broken Images, in which the character is in conversation with her doppelgänger. As directors found it challenging to take it on stage, Karnad took it on himself to direct it. Performed by Arundhati Nag, Karnad projected the doppelgänger through a television screen with a recorded performance and Nag enacted on stage as the real self interacting with her screen character. This unusual cross media experiment in theatre was well received and replicated in other languages.

Karnad’s film career has been equally illustrious. He started his film career by playing the lead role and writing screenplay for Samskara (1971) that dealt with the stalemate around performing the last rites of a Brahmin outcast. Based on UR Ananthamurthy’s novel, Samskara criticises the caste system, the orthodoxy, the ritualism and the corrosion of human values. Samskara became the harbinger of the Kannada new wave. Karnad made major contributions to the wave by directing Vamshavruksha (with B V Karanth), Kaadu and Ondanondu Kaaladalli. Karnad, together with Kasaravalli and Karanth, came to be called the ‘3Ks of the Kannada New Wave’. They heralded a new wave with a harsh indictment of caste system and Brahminism, sensitive portrayal of women’s oppression, and addressing adultery and taboos.

Ondanondu Kaaladalli, a medieval martial arts film, was inspired by Japanese director Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai and launched the film career of Shankar Nag, who went on to become a popular hero and director in Kannada cinema. Shankar Nag’s direction of Malgudi Days, a television serial, and Karnad’s performance as Swami’s father left an indelible impression on the Doordarshan audience. Karnad was also instrumental in introducing two major actors Om Puri and Naseeruddin Shah to films. As a versatile actor, Karnad acted in more than 50 films including Shyam Benegal’s Nishanth and Manthan.

If Kannada literature has a presence in national and international circuits, a major credit is due to Karnad, who during his seven year tenure at Oxford publishing house encouraged the publication of English translations of many writers. Works of mathematician, poet and theoretician A K Ramanujan gained popularity after Karnad published them in English.

As a public figure, Karnad was a rare personality harnessing his tall stature as a playwright, filmmaker, actor and intellectual to provide greater visibility to burning issues. He was fiercely outspoken and eloquent about his political stances, even on highly sensitive issues.

For the last three decades, ever since the Babri Masjid demolition, he had participated actively in protests against communalism, facing abuse and threats from the sanghis and Kannada chauvinists. When Hindutva fascists tried to turn the Bababudangiri shrine - the syncretic dargah of Baba Budan, who came from Arabia and introduced coffee cultivation to Karnataka, and is popularly believed to be the avatar of Dattatreya - into the Ayodhya of the South, Karnad and U R Ananthamurthy took a lead in forming a committee for communal amity. Karnad invited journalist Gauri Lankesh to join this committee (there were very few women on the committee), and with that began her experience of activism.

The killing of Pansare and Dabholkar in Maharashtra, where he was born, of M M Kalburgi, his contemporary in the Kannada literary world and of Gauri Lankesh, his friend and litterateur P Lankesh’s daughter - who had grown up in front of his eyes - deeply disturbed him. In the last few years, be it in support of Kanhaiya Kumar and Kabir Kala Manch, and against the institutional murder of Rohit Vemula and the lynching of minorities, Karnad made sure that his voice reached all over the country.

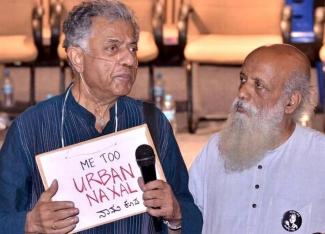

The image of Karnad, drawing oxygen through a pipe from a portable cylinder, with the placard #MeTooUrbanNaxal on his neck, will go down in the history as one of the iconic images of protest against saffron terror. At the age of 80, an ailing Karnad was slapped with cases for abetting or propagating naxalism for this act of solidarity. Hate messages, abusive calls, and death threats had become an everyday affair to him. He was foremost in the hit-list of the Hindutva fascist brigade. In fact, on one of the occasions, when Karnad shared the dais with Swami Agnivesh against communalisation in coastal Karnataka, the Bajrang Dal did the obnoxious act of performing ‘funeral rites’ for him. Karnad responded with his usual courage and wit, saying he would have been happy to take part in this event. It is no surprise that the Sanghis who held his funeral rites when he was alive, celebrated his death with congratulatory messages and abuse on social media. It is this obscene and grotesque ideology that seeks to kill opponents and celebrates their deaths, that Karnad fought with all his might till the end.

Looking back, if not for Karnad, certain interventions might not have been possible. In the 1990s, going against the tide of parochial sentiments, he dared to suggest that Karnataka should adhere to the Cauvery Tribunal Recommendations. There was a huge stir by Kannada chauvinists demanding that he leave the state. And two years ago, when the Sangh and BJP falsely declared the Tiger of Mysore Tipu Sultan to be an anti-Hindu tyrant, Karnad said that Bengaluru airport should have been named after Tipu Sultan. He faced a storm of abuse from the Hindutva forces for this. There are scores of such instances, including his condemnation of V S Naipaul's anti-Muslim views. Karnad even publicly regretted making films (in the early 1970s) based on the novels of Kannada writer S L Bhyrappa (who later joined the BJP), saying,“I regret doing such an injustice to myself and Bhyrappa as well. Bhyrappa’s novels were opposed to cow slaughter. I modified the content in the films I made since I am against a ban on cow slaughter.” Karnad was as outspoken in the field of literature too as he was on social and political issues. He didn’t mince his words in criticising Tagore and even UR Ananthamurthy.

In the theatre of democracy, Girish Karnad will be remembered for his bold and unwavering voice speaking truth to power! In life or death, Karnad remained a thorn in the side of the Sangh. And that is Karnad’s victory.

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

-

2011-2020

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

-

2019

- JANUARY-2019

- FEBRUARY-2019

- MARCH-2019

- APRIL-2019

- May-2019

- LIBERATION, JUNE 2019

-

Liberation JULY 2019

- One Nation, One Election: Attack On Federalism And Democracy

- No To Hindi Imposition

- Why Delhi - And India - Need Free Public Transport

- Encephalitis Epidemic in Bihar: Bihar and Central Governments Have Blood On Their Hands

- Why EVMs Must Go

- CPI(ML)'s sincere appeal to the Left ranks and democracy-loving, progressive people of West Bengal

- Modi 2.0 Regime : Intensified Attack on Working Class

- Himalayan Alpine Meadows Trampled For Wedding Tourism

- London Vigil For Sudan: Remembering Sudan’s fallen martyrs

- China: Thirty Years Since The Tiananmen Square Massacre

- Girish Karnad

- Comrade Subodh Kumar Sinha

- Red Salute to Comrade Rampadarath

- Vigil At Indian High Commission London Against Fascism and Hindu Supremacy in India

- Modi 2.0 Regime’s Assaults on Lawyers, Journalists, Intellectuals

- LIBERATION, August 2019

- Liberation, SEPTEMBER 2019

- Liberation, OCTOBER 2019

- Liberation, NOVEMBER 2019

- Liberation, DECEMBER 2019

- 2020

- 2021-2030

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org