THE Bihar and Central governments are guilty of criminal negligence in the prevention and treatment of Japanese encephalitis in Bihar. 125 children have died so far in Muzaffarpur and neighbouring districts of Bihar due to the Acute Encephalitis Syndrome (AES or ‘chamki fever’ as it is commonly called in Bihar).

Chronic Hunger Is At The Root Of AES Deaths

This disease strikes almost every summer since 1995 – affecting mostly the children of litchi harvesting workers and other poor labourers. Litchis are plucked early in the morning; and can contain toxins that can dangerously lower blood sugar. Children of the litchi harvesters, who eat a large amount of fallen litchis on an empty stomach to stave off hunger become especially vulnerable to AES, especially when they are already suffering chronic malnutrition, and fail to eat a hearty meal later in the day.

Simple preventable measures include washing the litchis before eating, and ensuring that the children are made to eat a full meal or even sugar mixed in water. And of course, experienced medical care and timely treatment can save lives once a child is affected.

In spite of being aware that this killer disease (which is preventable and treatable) strikes every season, the Governments of Bihar and the Centre have made no provision whatsoever to prevent epidemics and ensure the availability of timely and adequate medical care. The question arises – would Governments display such callous neglect if it were the children of the dominant classes and castes, instead of the children of daily wage agricultural labourers from oppressed castes, who were fatally struck down every year?

The Government has taken no measures to spread awareness about the simple measures that can protect a child from the disease. Litchi harvesting happens in summer, when schools are shut and so the mid-day meals are not available. The anganwadi system is also strained because of shortage of funds, ill-paid workers, and inadequate anganwadi centres, due to which it is unable to correct the chronic malnutrition and hunger that children suffer.

Dismal Health Infrastructure

Once the disease strikes, it quickly assumes epidemic proportions because there is no plan in place to keep it from spreading. And the affected kids keep dying in large numbers because of the dire shortage of hospitals at the village, Block and Sub-divisional level and the dismal condition of ICU and Emergency services even in District level hospitals. When a child is gripped by the encephalitis fever in a village, their condition deteriorates so much by the time they reach the hospital in the nearest city that it becomes impossible to save their lives.

Callous Governments

Meanwhile the Health Minister of Bihar, the BJP’s Mangal Pandey, displayed shameless callousness at a press conference on the epidemic, asking about the cricket scores. JD-U MP Dinesh Chandra Yadav defended Mangal Pandey by claiming that his concern with the cricket score in the India-Pakistan match proved his “nationalism”. The JDU MP also made light of the epidemic, saying “it happens every year, once the rains start, it will stop.” So in the BJP’s and JDU’s eyes, a preventable epidemic that kills poor children every year is not a “nationalist” concern but a cricket match is!

Public Health Network Not Ayushman Bharat Is Needed

The encephalitis epidemics in Gorakhpur (UP) and Muzaffarpur (Bihar) also underline how the Ayushman Bharat medical insurance scheme offered by the Modi Government is useless in tackling what ails healthcare in India.

In 2005, Dr Rama Baru of the Centre for Social Medicine and Community Health, JNU spoke to Liberation about the Japanese encephalitis epidemic in UP. Nearly 2 decades later, nothing has changed, because no lessons have been learned.

Dr Baru had stressed that the issue could not merely be to provide individual citizens access to hospitals. To predict and therefore prevent the outbreak and spread of communicable diseases and epidemics like encephalitis, malaria, gastroenteritis, etc, a robust public health infrastructure for surveillance and monitoring of diseases. Without such public health infrastructure, it is impossible to interrupt the cycle of transmission of communicable diseases.

In Kerala, where the public health infrastructure is relatively more robust compared to other states, we saw how the Nipa virus epidemic could be contained. Privatisation of healthcare across India, and the resulting weakening of public health infrastructure has inevitably weakened the ability to predict and prevent communicable diseases.

Epidemics Are Caused By Chronic Hunger

Further, Dr Baru made the point that epidemics always affect the weakest sections of society worst – the tribals, the Dalits, the landless workers, who are vulnerable because they suffer chronic hunger, malnutrition, and joblessness. To understand epidemics, we must put hunger, joblessness and deprivation back in the picture.

Ayushman Bharat - the Modi Government’s answer to India’s healthcare crisis – is a medical insurance scheme that will siphon off public funds towards private healthcare providers. It will only further promote the dismantling of India’s public health system with private healthcare providers. It will only loot the poor through premiums they can ill afford, while failing to ensure timely and effective treatment to patients locally. And of course, it is no answer to chronic hunger and the resulting diseases and epidemics. What we need instead is a stronger public health system providing free and excellent healthcare for all, ensuring monitoring and prevention of epidemics, and ending chronic hunger. If we do not demand and achieve this, the killer epidemics we have seen over and over in India's villages and cities will keep being repeated.

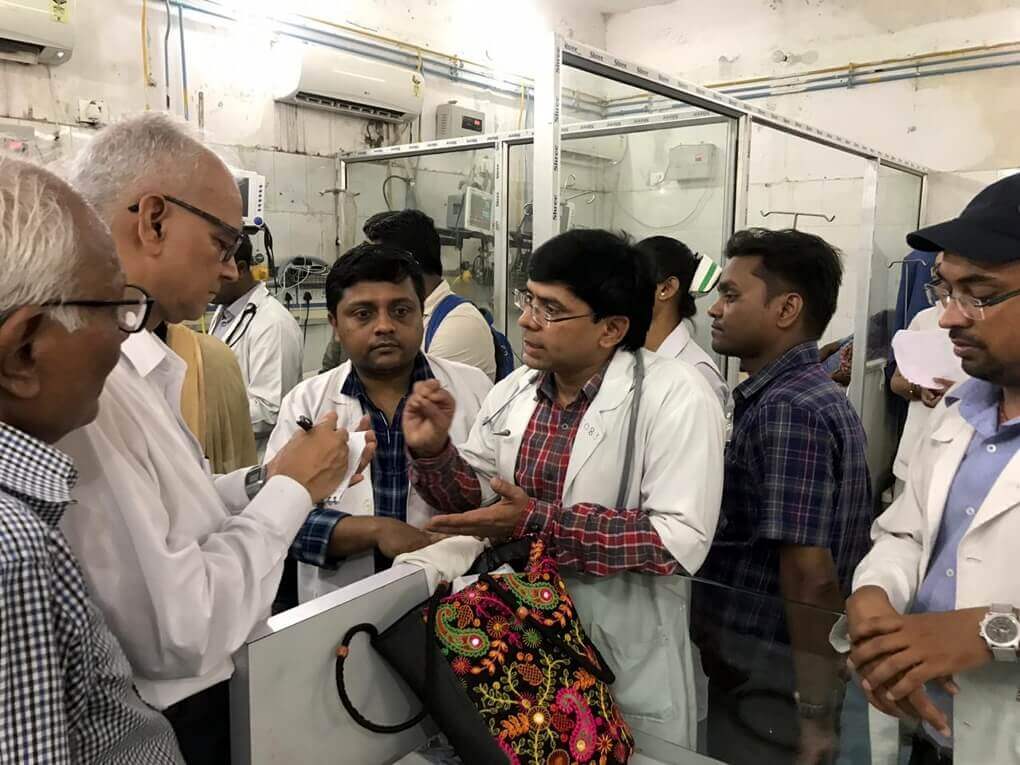

CPIML Fact-Finding Team Visits SKMCH Muzaffarpur

A State level CPI(ML) team led by Bihar State Secretary Comrade Kunal visited SKMCH at Muzaffarpur on 19 June 2019 and took stock of the situation. The team visited the children admitted in the PICU (Paediatric Intensive Care Unit) and the wards and spoke to the family members. It also met the Hospital Superintendent and the Paediatrics Department Head and discussed the subject of prevention of encephalopathy which has taken the form of an epidemic here. Earlier, a CPI(ML) team led by MLA Mahboob Alam also visited Muzaffarpur.

Three major points came to the fore requiring immediate initiatives and measures:

Increasing the ICU Bed Capacity to 200

The hospital had a 14-bed PICU which has now been increased to 50 beds. But even this is not sufficient as there are currently 96 children admitted in the hospital which means that there 2 children in one bed. The Superintendent said that all children could be treated properly and get relief if the number is increased to 200 beds.

Doctors, Medicines and Ambulances at Primary Health Centres

The second suggestion made by the team of doctors was that the condition of Primary Health Centres should be put right and doctors in large numbers should be appointed at these Centres. If the children reach the Health Centres within 3 hours, it is much easier to save them. Medicines and ambulance services should also be arranged at the Health Centres.

Clean Water, Maintenance of Glucose Levels

The third suggestion was to attack the source of the disease. The government should make arrangements to ensure regular supply of clean water. If the glucose levels of the children is maintained properly and proper arrangements for food and nourishment are made for this, this epidemic can be controlled.

The team found that so far 372 children have been admitted to SKMCH, of whom 93 children have died. The death rate is 25% which is extremely dangerous. The hospital has a total of 21 paediatric doctors (10 doctors have presently been called in from outside); whereas there should be 1 doctor for every 2 or 3 children, and as per 8-hour duty there should be 90 doctors. There is also a shortage of paramedical staff and nurses. Some have been called in from other wards, due to which those wards are also facing a crisis.

The AC in ICU No. 3 was not working; 3 out of 5 generators are not working; the children who are removed from the PICU are sent to wards where not even a fan is available. The children are dying as much, if not more, due to negligence than to disease. The disease is known but not even basic facilities and arrangements are available. At the Primary Health Centres (PHCs) neither paediatricians nor ambulance services are available.

The enquiry team comprised Comrades Kunal, Rajaram Singh (All India Kisan Mahasabha GS), Muzaffarpur District Secretary Krishna Mohan, City Secretary Suraj Kumar Singh, State Committee member Shatrughan Sahani, Insaf Manch leader Fahad Jama, State Councillor Aftab Alam, RYA District Secretary Rahul Kumar Singh, AISA District Secretary Vikesh Kumar, and District Committee member Rambalak Singh.

The CPIML has demanded that the Nitish Kumar Government sack Health Minister Mangal Pandey, and deal with this killer epidemic on war footing, recognising it as a public health emergency. The party demanded urgent measures to prevent the further spread of the epidemic, deployment of additional doctors and health workers to save the children of Bihar, and ICU services in District hospitals and Emergency services in Block level hospitals.

Muzaffarpur Health Infrastructure Is Nearly Non-Existent

(Source: ‘No Muzaffarpur medical centre has a rating better than zero’, Rema Nagarajan, Times of India, June 20, 2019)

While the state and Union governments are now scrambling to deal with the outbreak of acute encephalitis syndrome (AES) disease in Bihar's Muzaffarpur, official data shows the shocking state of the public health infrastructure in the district. The health ministry's health management information system (HMIS) shows that all of the 103 primary health centres (PHC) and the only community health centre in the district were not considered even fit for evaluation or were rated 0 out of 5.

The mandatory requirements for a PHC to be evaluated under HMIS were that if it is a 24x7 centre, it has to have at least one medical officer, over two nurse-midwives and a labour room. For non-24x7 centres, all that was needed was at least one medical officer and one nurse. Yet, 98 of the district's 103 PHCs could not meet even these minimum requirements and hence were not graded in the 2018-19 evaluation.

At least 98 of Muzaffarpur district's 103 primary healthcare centres (PHCs) could not meet even minimum requirements. Of the remaining five, every single one got a zero rating. The rating consists of three points for infrastructure and two for services. Thus, each of the five failed miserably on both counts.

Incidentally, according to the official norms, there is supposed to be one PHC for every 30,000 population in the plains. By that count, Muzaffarpur should have had over 170 PHCs for its population of a little over 5.1 million.

The situation of the lone community health centre (CHC) was no better. In the 2017-18 rating of CHCs, the one in Muzaffarpur was rated "not eligible". This is because it failed to meet the mandatory criteria required for being rated.

What were these mandatory criteria? In terms of staffing, there should have been two or more doctors, six or more nurses or ANMs (auxillary nurse-midwife) and at least one lab technician. As for infrastructure, there should be an operation theatre, a generator and separate "public facilities" (read toilets) for men and women.

Again, Muzaffarpur's population should have meant it should have at least 43 CHCs, given the norm of a CHC for every 1.2 lakh population in the plains. Instead, there is just one and that in a shape that does not even merit evaluation.

What makes this situation particularly shocking is that the district has been witnessing deaths of scores of little children at this time of the year every year for the last two decades or more. And yet, successive governments have not bothered to beef up the public health infrastructure to cope with even routine health needs, leave alone a medical emergency they know will hit unfailingly each year.

Empty Promises

(Source: ‘Encephalitis Deaths: Bihar’s Healthcare System in ICU’, Tarique Anwar, Newsclick, June 20, 2019)

After visiting SKMCH in 2014 after the death of 139 children, then Union Minister Harsh Vardhan had said that the government would increase the number of MBBS seats from 100 to 250 but nothing has happened so far. In fact, the Medical Council of India (MCI) had decreased the number of seats to 50 because of poor infrastructure. This was increased to 100 in 2014, after the deaths.

Nitish Kumar was also chief minister in 2012 when 179 children died, and he was again chief minister in 2014, when 139 children died. A seven-year period was enough to equip the hospital with latest technologies and fulfill all the requirements.

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

-

2011-2020

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

-

2019

- JANUARY-2019

- FEBRUARY-2019

- MARCH-2019

- APRIL-2019

- May-2019

- LIBERATION, JUNE 2019

-

Liberation JULY 2019

- One Nation, One Election: Attack On Federalism And Democracy

- No To Hindi Imposition

- Why Delhi - And India - Need Free Public Transport

- Encephalitis Epidemic in Bihar: Bihar and Central Governments Have Blood On Their Hands

- Why EVMs Must Go

- CPI(ML)'s sincere appeal to the Left ranks and democracy-loving, progressive people of West Bengal

- Modi 2.0 Regime : Intensified Attack on Working Class

- Himalayan Alpine Meadows Trampled For Wedding Tourism

- London Vigil For Sudan: Remembering Sudan’s fallen martyrs

- China: Thirty Years Since The Tiananmen Square Massacre

- Girish Karnad

- Comrade Subodh Kumar Sinha

- Red Salute to Comrade Rampadarath

- Vigil At Indian High Commission London Against Fascism and Hindu Supremacy in India

- Modi 2.0 Regime’s Assaults on Lawyers, Journalists, Intellectuals

- LIBERATION, August 2019

- Liberation, SEPTEMBER 2019

- Liberation, OCTOBER 2019

- Liberation, NOVEMBER 2019

- Liberation, DECEMBER 2019

- 2020

- 2021-2030

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org