IN the life of a revolutionary it is always painful when some comrade take their leave forever, leaving you to carry on his unfinished task. But I find it hardest to bear with the fact that someone who has been travelling all along with me for around half a century is no more beside me. Twenty years back it was VM and now DP Bakshi.

I first met Bakshi in 1966 when I along with Vinod Mishra entered Regional Engineering College, Durgapur in the first year in the mechanical engineering course. Dhurjati Prasad Bakshi, who was to be later widely known in the Party as Pranab, was a civil engineering student. Although he had entered college in 1965, he was victimised in the first year by the authoritarian administration. He had complained about some irregularities in the hostel mess functioning and that was construed as a sign of indiscipline or disobedience. Consequently he was made to repeat the first year and that is why he was with us in the first year in 1966-67.

I first met Bakshi in 1966 when I along with Vinod Mishra entered Regional Engineering College, Durgapur in the first year in the mechanical engineering course. Dhurjati Prasad Bakshi, who was to be later widely known in the Party as Pranab, was a civil engineering student. Although he had entered college in 1965, he was victimised in the first year by the authoritarian administration. He had complained about some irregularities in the hostel mess functioning and that was construed as a sign of indiscipline or disobedience. Consequently he was made to repeat the first year and that is why he was with us in the first year in 1966-67.

In the year 1965, when Bakshi entered RE College, Bengal as well as the whole country was passing through a period of turmoil that has been described in Comrade Charu Mazumdar’s celebrated Eight Documents, particularly ‘What is the source of the spontaneous revolutionary outburst in India’ where he speaks of people’s resistance to tram fare hikes and the anti-hoarding movement ‘Dumdum Dawai’. Coming from Chunchura of Hooghly district, Bakshi had spontaneously imbibed this spirit of rebellion. The influence of the heroic liberation war in Vietnam had resonated in Bengal through slogan ‘Amar naam tomar naam, Vietnam, Vietnam’. It is because of this rebel nature that he protested and was victimised.

However, our intimacy did not grow immediately in the first year because I and VM were from a non-Bengali background entering college through IIT entrance exams, whereas Bakshi was Bengali and entered through the Bengal engineering entrance route, and moreover our branches as well as sections were different. Hostel wings were also different. But an incident brought us into contact in the first year itself, when he first came to mobilise us for a flash strike to demand revocation of rustication of a student from the college. Before this, a strike had never taken place in our college history.

In fact there was a barrack-like atmosphere where students were asked to wear proper dress with boots not only in the class, but also in the mess, keep their things in order, even fold mosquito net properly, otherwise if found defaulting during the inspection they would be rebuked and fined. Absent students too were fined and then warnings were issued as a custom and letters were sent to parents to keep their wards under discipline. Even for minor offences they were made to repeat years or even rusticated. All this was in the name of maintaining college elitism where future engineers were to be cast as if in a foundry!

But the atmosphere outside the college was radicalising rapidly and students were getting restive against this regimentation. When all of the sudden students launched the strike and did not go to attend college in the second shift, the administration was taken aback. Already a known rebel, Bakshi was one of the leading students who came to mobilise first and second year students. When the students did not budge even after threats of disciplinary action, the rustication was withdrawn after negotiations.

Before the second year started, the Naxalbari uprising had already taken place and its impact was soon felt in the college campus. The word Naxalite had already been ringing in our ears and Mao’s writings became popular among us. We had started identifying ourselves as radical left or Naxalite sympathisers. In this atmosphere one of our fellow students Debasis was elected Literary Secretary of College Gymkhana (there was no students union and the Gymkhana functioned under the guidance of a professor in-charge). The Gymkhana literary department used to publish a yearly magazine called “RECOL Speaks”. VM along with other left students leaders, including a senior student Gautam Sen, decided to change the name of the magazine to “Vanguard” and gave it a radical direction. In the magazine the key slogan was Mao’s famous quote “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun”, and there were articles about students’ radical role in changing the society. In this magazine Bakshi wrote a satire piece about ‘police fleeing the campus leaving their cap behind’. The incident had taken place in the beginning of the year when a police posse had come sneaking into the campus and when students chased them away one of the policeman left his cap behind while fleeing.

The publication of Vanguard was taken as an attempt of Naxalite takeover of campus politics by the authorities and some reactionary minded students, and consequently a sharp polarisation ensued. The authorities suspended the publication and rebuked the literary secretary asking him to suspend further activities. In the meantime a good number of first year students had also joined our camp. Some adversaries from the third year burned the copies of Vanguard and tried to beat the first and second year students who supported Vanguard. Bakshi and VM bore the brunt of their physical attack and also mobilised counter resistance. But the balance of forces had not yet tilted in our favour. However, this incident helped us in expanding and consolidating our base.

The strike that took place in the second year did not succeed because the authorities cunningly declared sine die. Messes were closed and students’ were asked to leave their hostel and issued concession forms to go back to their homes. Letters were sent to their parents as well telling them to advise their wards not to participate in strike activities and send them back only when asked by the administration. With the hostels vacated, the students could not carry on their fight and ultimately everybody left. A handful of students like Bakshi and VM remained there and tried to stop students but in the absence of proper strategy they failed. But this failure was a lesson that we applied in the third year strike. This time, however, their success in overcoming the student resistance gave authorities renewed confidence to discipline them once again.

In the third year, the leftwing camp had earned sufficient strength to command a successful strike. The balance of forces had turned and gradually RE College was being considered a Naxalite base even outside the campus. We won almost all key posts in the college Gymkhana. The administration had strictly imposed an attendance requirement for appearing in the exams and several students were debarred from appearing. An adamant administration did not heed the students’ demand for reconsideration and a strike ensued.

A Strike Committee was formed and teams were formed in every hostel to persuade every student not to go home in case the administration closed the college sine die. Bakshi played his leading role in managing all this. Ultimately the authorities were gheraoed by the students and consequently surrendered. The strike was totally successful and the administration agreed to comply with all the demands. This broke the stranglehold of the administration for good and college was declared as a ‘liberated zone’! Needless to say that this was because of radical left camp of the students that had grown sufficiently powerful by that time. Bakshi was always and everywhere in the leading role during this struggle and earned immense popularity and respect among the student in the course of these movements.

Another fact worth mentioning here that Bakshi, who was popularly called Suji, a name that was given to him by fellow students, was elected Mess Secretary. He was so popular that he was elected unopposed. He established close contact with the mess workers and politicised them. Gradually all mess staff turned our supporters because we guarded their interests and resisted the unruly behaviour of bullying students. It was here that Bakshi showed his rare quality of integrating with the working class even while studying in the college. He recruited one whole timer from among the mess boys who later left the college and later became Party secretary of the Chittaranjan local committee. Bakshi was also active in mobilising the security and even clerical staff of the college.

These days, a good number of copies of Deshabrati were regularly brought to the college and for that one of us would go to Kolkata every week. This raised the political consciousness and partisan spirit among the leftwing students. Meanwhile AICCCR had been formed and we established links with the district organisation. Bakshi had local contacts and used to meet local worker comrades outside the campus in Durgapur, while our expansion outside was limited to peripheral areas. We participated in wall writing and postering under the banner of AICCCR and participated in processions in solidarity with workers movement, particularly against state repression. Towards the end of third year we started thinking of becoming professional revolutionaries and discussed whether or not to write our exams. However, ultimately as suggested by the local organisation, we appeared in the exams. We had formed secret cells recruiting potential whole timers. Bakshi was one of the first students to express his willingness to go to the countryside.

Meanwhile an incident took place towards the end of third year when examinations were going on. Students used to go outside the campus to take tea near the GT Road. A police outpost was situated nearby. On pretext of some minor quarrel between students and policemen, two of the students were arrested. Hearing the news, students in large numbers went to the outpost and demanded their release so that the students could give their exams. But instead of releasing them, a sub-inspector came to talk with students. Students lured him into the hostel and took him into their custody. The outpost police did not dare entering hostel. Ultimately with the intervention of the principal, both students and the sub-inspector were released.

But the police authorities were not pleased and wanted revenge. A day after the incident, when the exams were going on, a large contingent of police entered the campus and started firing without any provocation. A first year student Prakash Poddar was killed by police bullets. The police also resorted to lathicharge and even entered the hostels, leaving scores of students injured. Those days the CPI(M)-led United Left Front government was in power and the ruling party was not pleased with the spread of Naxalite influence in RE College.

Naturally, this incident intensified our hatred against the state and the ruling regime. Memoranda were submitted on behalf of the students to the governor as well as union home department protesting the police atrocity and demanding an enquiry. However, the government of the day did not respond positively.

Entering the fourth year, all of us who had decided to work as whole timers stopped attending classes. Towards the end of April, after we finished our third year exams, CPI(ML) had been formed. Charu Mazumdar’s call for leaving the college and jumping into the class struggle had reached us. That year we did not participate in any gymkhana elections, but a strike is worth mentioning here. It was not a students’ strike, but a strike of mess workers launched under our encouragement for wage rise and better living conditions.

The college authorities closed hostels and asked students to go home. It was difficult to stop students this time because it was not their direct interest that was at a stake. However, we tried to mobilise as many students as possible and demanded mess facilities as we want to stay and pursue studies. In fact we had decided not to go home. This was to pressurise the administration to accept mess workers’ demands. Around 40 or more students stayed and gheraoed the board room where the principal along with the staff had to listen our demands. During this period we managed to cook ourselves with the help of mess workers. Bakshi was a key figure in this movement. Ultimately negotiations took place and students were called back and the mess resumed its operation. In this movement, security workers and even sympathetic teachers helped us.

We realised we had had enough of study and struggle in this engineering pathshala. Now it was time to move out to larger pathshala of the earth, the pathshala of life and basic class struggle. Soon we started leaving the college campus and the Party deputed us to different areas. I remember that the first person to go out in the late 1969 was Bakshi himself. He was sent to work in the coal belt and rural areas in Ukhra block of Bardhaman district. A few months later I was posted in the nearby industrial belt of Asansol. Working in underground conditions we could not know much about each other.

However in May 1970 we once again met in the RE College when the Deshabrati office was raided and the publication went underground. We had to print cyclostyled copies from the text sent to us from our Party centre. Bakshi had come to collect some copies for his area.

Those days there was an industrial zonal committee comprising the whole industrial belt of Bardhaman district, from Durgapur to Chittaranjan and even including Kumardhubi-Nirsa coal belt of now Jharkhand.

Subsequent to the First Congress of CPI(ML) in May 1970, when fresh ideological struggle broke within the Party and Comrade Saroj Datta replaced Comrade Sushital Raichaudhury as West Bengal State Party Secretary, Comrade SD attended meetings all over Bengal. In this course he visited our industrial zonal area and an extended meeting was organised. When I reached the venue I found it was Bakshi who had organised the meeting in his area. During underground days holding such large meetings in the villages was not possible without total support of the local peasants and workers who not only supplied food and shelter but also kept a constant vigil during the meeting. I found that Bakshi had fully integrated himself with the local population comprising coal-workers and poor peasants.

Till mid 1973 when I worked in the industrial belt there were chances to meet Bakshi, often in Durgapur shelters where we used to visit to maintain contact or hold meetings. But after that I went to work in Bihar and lost contact with him. During the Emergency he was arrested from Durgapur and it was only after his release that could meet with him sometimes in 1978 or ’79. He had a severe leg injury due to police torture and because of neglect in treatment and care now, could only limp. Despite all the care that could then be managed within underground shelters, it could never be fully cured. After working in West Bengal for some time, he was sent to Assam.

Bakshi had a good memory of the college days and sometimes when we met we used to recall those days. He had maintained contacts with many of our classmates which I could not do, but he kept me informed about them. Sometimes he visited them and made some of them subscribers of Liberation to keep them in touch with the Party. It was because of this that some of our college mates came to attend his memorial meeting held on 17th and some of them recounted his role those days in the students movement.

Whenever we met Bakshi used to tell me about his experiences in various states, including Assam, Jharkhand, Odisha and southern states, where he had worked as Party incharge. He also kept me informed about developments in working class front. His extraordinary organising skill has been widely appreciated. He used to create a friendly and homely atmosphere wherever he went to work. Apart from male comrades coming from various strata of the society, he could particularly mix as a friend with women comrades and sympathisers, as well as children. As a result everybody could talk freely with him regarding his or her problems.

What was particular about him was the fact that wherever he went to work, he tried to go deep into the cultural roots of the society and understand its dynamics. It was he who acquainted me with the cultural history of Assam, from Sankardev to Vishnu Rabha and Jyotiprasad Agarwala. Not only Assam, he had acquired a fair knowledge of various tribes of Northeast India, their cultural traditions, and tried to forge contacts with the progressive elements within these communities. He had an inspiring role in building Sadau Asom Janasanskritik Parisad and publication of party magazine Bikalpa and women’s magazine Aider Jonaki Bat. Similarly he took an interest in understanding the tribal communities of Jharkhand. His great initiative in organising a mega cultural event of Jharkhandi culture is still remembered, in which he endeavoured to mobilise intellectuals, cultural activists, folk singers and performing artistes from all over Jharkhand.

Bakshi wrote many articles for Liberation and Deshabrati on various topics. His language was jargon free, quotation free and easy to grasp.

During the last ten years I got more opportunities to talk to him as he often came to Patna to attend meetings of the Party core among government employees, railways and construction workers. He always brought Bengali literature with him for me and some other material, including his own articles written in Bengali, for translation and publication in Lokyuddh.

We used to recall and reevaluate our past, discuss the mistakes we had committed as well as the successes achieved in our shared past. He invited me to visit Nirsa-Kumardhubi area as well as Asansol where I had worked earlier, but I could not fulfil his wish in his lifetime. During his last days he was incharge of the newly carved out industrial district of West Bardhaman where a new district committee was to be formed. Recalling the martyrs of the region in the early 1970s (including one of our classmates Tapan Ghosh, who was martyred during the unsuccessful Asansol jail break) he promised that he would arrange for me to meet with Asansol comrades. It was only after attending his last journey on 27 July that I could go to Asansol where I attended the 28 July martyrdom day meeting. Along with Charu Mazumdar we also paid tribute to Bakshi in that meeting.

After attending the CC meeting held in Ranchi at the end of June, Swadesh Bhattacharya and I went to see him in SSKM hospital in Kolkata, where he was fighting his last battle. He recognised me and asked whether I was still looking after Lokyuddh. But I was surprised when he recalled at that hour, the story of how I escaped arrest in Asansol in the early 1970s, an event only he could know!

Adieu dear Bakshi, you will forever live in my memory.

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

-

2011-2020

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

-

2018

- January-2018

- February-2018

- March-2018

- May 2018

- June-2018

- July 2018

- August 2018

- September 2018

-

October 2018

- Thus Spake Bhagwat: Making Hay While the Sun Shines

- Bhagwat's Speech And RSS Ideology: A Closer Look

- JNU Fights Back And Inspires

- The JNU VC Needs To Go Before He Destroys JNU

- Not a Clash or a Gang War, Onus of Violence in JNU on ABVP

- Ordinance Criminalising Instant Triple Talaq Violates India's Uniform Criminal Code

- Rainbow of Hope In Dark Times

- Marxism, The Bolshevik Revolution and LGBT Liberation

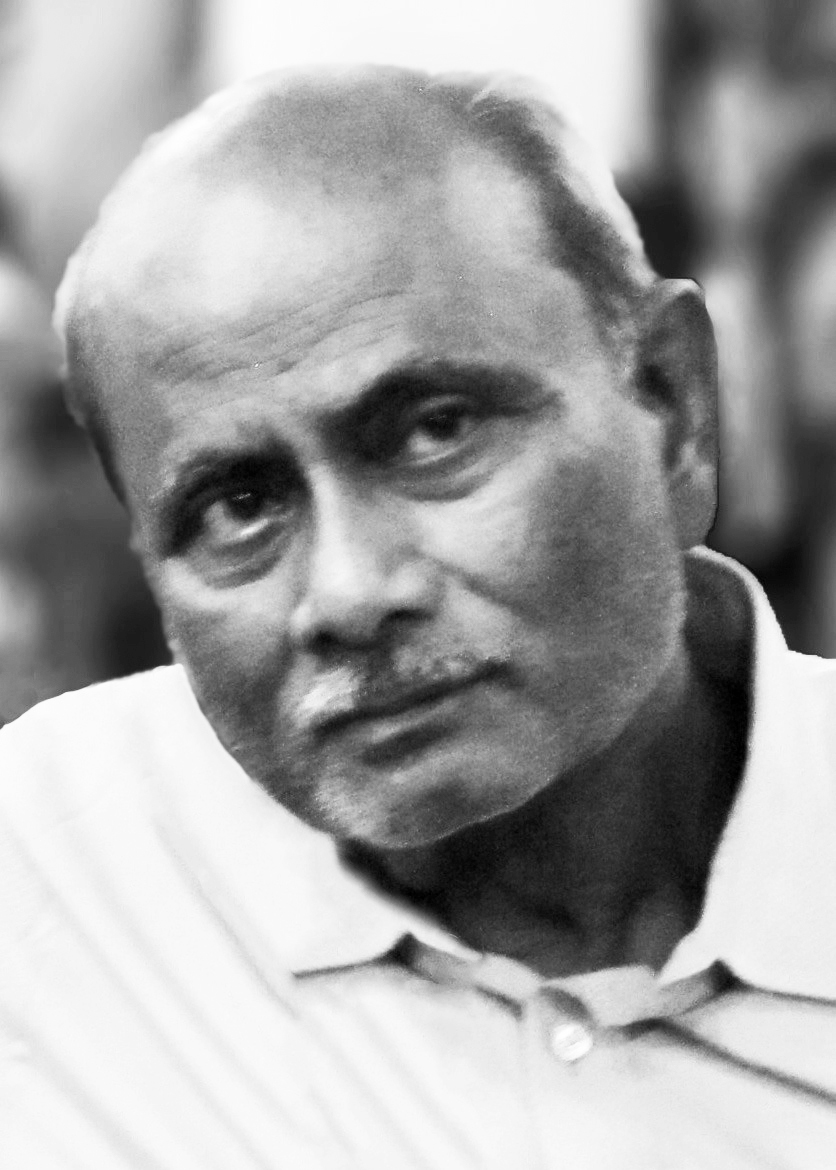

- Comrade D P Bakshi

- Modi Government's Ploy To Divert And Rule

- Fascist BJP Down Down!

- Modi Government's Massive Corruption Scandals

- Is This Freedom?

- Kondapalli Koteswaramma: A Century of Struggle

- Shamsher Singh Bisht

- Adieu Vishnu Khare

- Bangladesh Garment Workers Protest Against 'New' Minimum Wage Rate

- CPI(ML) Comrades' Flood Relief Work In Kerala

- Questions You Want To Ask - And PM Modi Doesn't Want To Answer!

- November 2018

- December 2018

- 2019

- 2020

- 2021-2030

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org