(Article by JNU faculty member Dr Parnal Chirmuley in Indian Express, November 21, 2019)

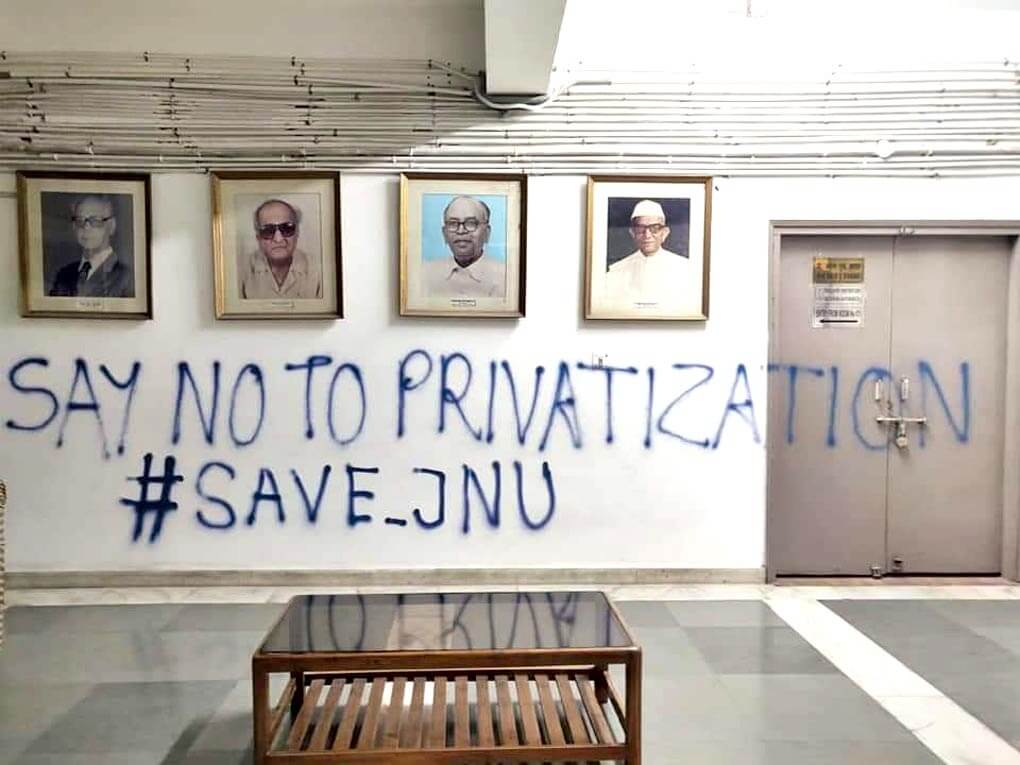

UNIVERSITY students and faculty speaking up for publicly-funded higher education have been the object of intense vilification in sections of the media and the general public countless times in the past few years. And yet, they refuse to fade away, spilling out of campuses, fighting for equitable access to publicly-funded higher education. They refuse to be shamed into submitting to education policies that exclude large sections of the population to make way for the elite few. The background to their persistence needs to be sketched out, especially because trained and paid armies of trolls continue to plague the discourse on higher education with vitriol and lies.

The attempt to construct stereotypes of students in the public sphere as lazy, good-for-nothings who want to survive on the taxpayer’s money is a clever sleight of hand by the ruling party and its offspring. Students of research universities like JNU are repeatedly castigated, supposedly by a “taxpaying public” for not earning their own living and paying fees. The argument is that money spent on their education is “a waste”. It helps obfuscate the true nature of education policies by this government.

It seeks to draw your attention away from the fact that equitable access to inclusive higher education actually transforms lives for the better, wherein a street vendor’s child, a former chowkidar, a young woman from a slum in Mumbai can each seek an education that helps them climb out of the pit of deprivation and achieve intergenerational mobility. For a ruling dispensation that stands triumphant on the shoulders of social divisions based on caste, gender, and religion, this disruption of inequality is frightening. And, this is why you are being relentlessly fed these stereotypes so that you will continue as passive participants in the drama of the oppression of the marginalised and the underprivileged.

Here are a few facts that might help us to cut through the vitriol and ask some hard questions: According to the CAG Report of February 2019, Rs 94,036 crore of the secondary and higher education cess and Rs 7,298 crore of the research and development cess remained unutilised. Where will this money go? The fee hike in JNU (which has led to massive protests in recent weeks, bringing down upon our students the wrath of paramilitary and police), if implemented, will lead to over 40 per cent of our students being completely abandoned by the education system, and render JNU as one of the most expensive public universities in the country.

Here, the question of where the taxpayer’s money is going can be sharpened: In 2017-18, the total expenditure on JNU was Rs 556 crore, seeing over 8,000 students through one academic year, over a 1,000 research articles published in reputed journals, 1,086 special lectures being open to the public, and 4,594 MPhil and PhD dissertations being submitted. Contrast this with the Rs 1,313 crore spent on mere publicity of the central government and its schemes. The imbalance in priorities is crystal clear. In JNU, some 2,500 students with fellowships pay Rs 7,500 (Rs 22.5 crore per annum) per month as housing allowance to the university. In the last two years, Mphil/PhD (especially reserved) seats have been left vacant, despite the Delhi High Court castigating JNU for causing a national waste of resources. The struggle against seat cuts now joins the struggle against fee hike to make the same point over and over again — the decimation by the present government of the inclusive and representational higher education for all.

A deeper reflection of this imbalance is the National Education Policy (NEP) 2019, which is really what students in JNU and across campuses are fighting against. This policy is nothing more than a deliberately planned eclipse of equitable access to publicly funded education. Here is why.

The setting up of the Higher Education Funding Authority (HEFA) by this government to replace the University Grants Commission (UGC) requires that institutions of higher education function not on grants, but on loans that are to be recovered through fee hikes and other “internal resource generation”, a pseudonym for placing education in the marketplace rather than at the disposal of the social good. The vision and the methods of the NEP 2019, which is built on the fundamentals of the HEFA, have nothing to do with universal humanistic values that underlie education policies in many countries where human rights, bridging social, economic, and regional chasms are the objectives of education at all levels. In fact, in many of them, university education is free, even though the average per capita income is far higher than in India. In these imaginations, the subject is defined by her rights and her needs. Moreover, the Constitution of India requires that education policy provide for equitable access to publicly funded education.

The NEP 2019, however, has little beyond the so-called “Fourth Industrial Revolution” as the driving impetus, in which, the individual is seen as mere kindling in the fire of economic activity. It sees no other function to education other than producing cheap labour that toils away on the lowest rung of the labour ladder.

It renders complete the shift from education as a right to education as a commodity. In the real world, in real-time, this policy casts a highly porous net that will benefit but a small section of the population that can buy education from private profiteers, rendering even basic education an unaffordable luxury. Increasingly, the bottom of even the social section that believes it might be able to afford this luxury is also falling out, given the state of the economy where unemployment is the highest in 45 years. In the absence of publicly-funded education, parents and students will be driven in the direction of education loans and a lifetime of indebtedness. This puts education out of the reach of even the middle classes.

This is why students in universities like JNU are at the barricades, in a movement that is spreading like a necessary conflagration through campuses in the country, for they want to ensure their own rights and pay it forward, so that coming generations can rightfully seek solid and affordable education instead of choosing between indebtedness and illiteracy. We need to listen to them, now.

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

-

2011-2020

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

-

2019

- JANUARY-2019

- FEBRUARY-2019

- MARCH-2019

- APRIL-2019

- May-2019

- LIBERATION, JUNE 2019

- Liberation JULY 2019

- LIBERATION, August 2019

- Liberation, SEPTEMBER 2019

- Liberation, OCTOBER 2019

- Liberation, NOVEMBER 2019

-

Liberation, DECEMBER 2019

- Ayodhya Verdict: Secular India Has Lost The Legal Battle, Must Win The War

- Modi PMO Introduced Electoral Bonds, Repeatedly Broke Laws – So That Black Money Could Fuel The BJP

- Relevance Of Guru Nanak Dev's Teachings To Society Today

- Support JNU Movement! Keep Doors of Universities Open For The Poor And Marginalised!

- JNU Students Beaten, Arrested For Peaceful Protest - ABVP Thug Free After Trying To Set Teachers On Fire

- Why We Must Listen To JNU

- Diversity, Democracy and Dissent: JNU

- Courage Confronts Brute Power

- Solidarity With JNU

- Students Are Rising in Pakistan

- Kerala Extra-judicial Killings

- Landless Dalit Youth Brutally Murdered in Sangrur

- Farmers' Struggle in Punjab Wins Justice

- Interfaith Couple Harassed By Communal Forces in Chhattisgarh

- Boiler Blast Kills Mid-day Meal Workers in Bihar

- Hindustan is proud of Pandit Firoz Khan

- Save Kalyanalova Reservoir

- BJP Tries To Meddle In UK Polls

- People's Movement in Chile Demands New Constitution

- Protests Force Ecuador To Withdraw IMF Austerity Package

- Coup In Bolivia Followed By Massacre of Indigenous Peoples

- Comrade Gurudas Dasgupta

- 2020

- 2021-2030

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org