“HOW many times can a man turn his head/ And pretend that he just doesn't see?” How many times can we, as Indians, turn our heads and pretend not to see the terrible tortures inflicted on the people of Kashmir?

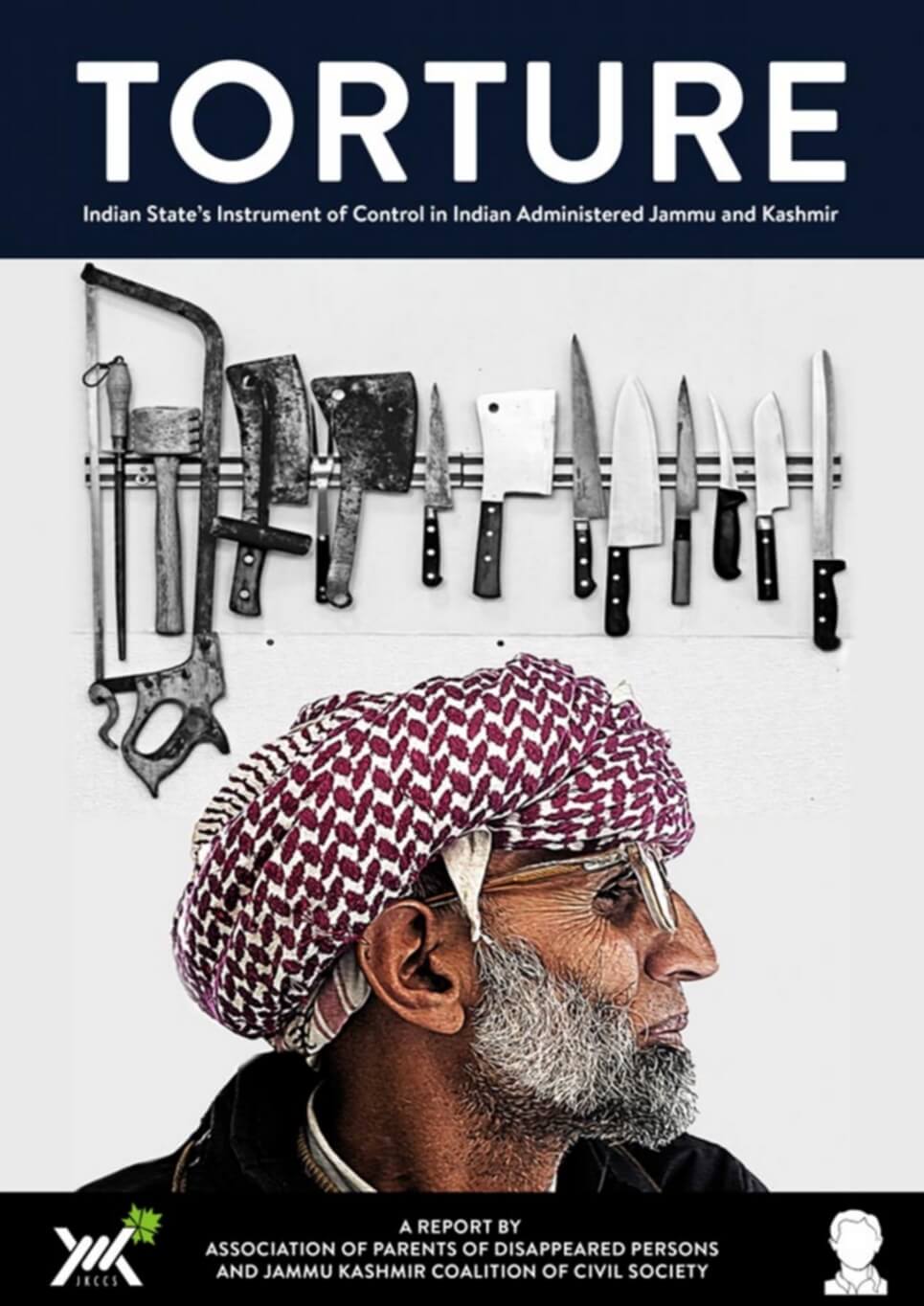

Torture: Indian State’s Instrument of Control in Indian administered Jammu and Kashmir (2019), published by Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) and Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) is the first ever comprehensive report on the phenomenon of torture in Jammu and Kashmir perpetrated by the Indian State from 1990 onwards.

Torture: Indian State’s Instrument of Control in Indian administered Jammu and Kashmir (2019), published by Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) and Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS) is the first ever comprehensive report on the phenomenon of torture in Jammu and Kashmir perpetrated by the Indian State from 1990 onwards.

Not long ago, in a letter dated March 18 2019, three special rapporteurs of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) wrote India asking for details on steps taken to punish or provide justice to victims and their next of kin in 76 cases of torture and arbitrary killing in J&K since 1990. India refused to engage with these three special rapporteurs claiming they displayed “individual prejudice.” Earlier India had also dismissed the UN OHCHR report on human rights violations in J&K as baseless. But such empty and generalised denials and dismissals only add to the weight and urgency of reports such as the latest one documenting custodial torture. Indian citizens must not look the other way and ignore these well-documented reports of terrible atrocities committed in the name of our country.

The report begins by citing a long list of incidents of torture from the last couple of years:

“On September 5, 2018, Feroz Ahmad Hajam from Kokernag was arrested from Khanabal by SOG personnel, who first took him to Joint Interrogation Centre (JIC) Khanabal, then to the Rashtriya Rifles (RR) Camp in Kapran Anantnag and finally to the 19 RR Camp Nodura, Anantnag. At this camp the SOG personnel slit his throat, holding him from behind and damaged his vocal cords severely so that he won’t be able to speak again. On July 1, 2016, Irfan Ahmad Dar of Qaimoh, Kulgam was severely beaten by personnel of the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) while he was trying to save his 12-year-old brother from being beaten. Irfan died on July 14. On July 10, 2016, Hilal Ahmad Parray of Tengpora was beaten by CRPF personnel. He died in the hospital on July 16. On July 20, 2016, Ghulam Mohi-ud-Din Mir of Lolab, Kupwara was tortured to death by the Army’s 41 RR regiment. Ishfaq Ahmad Dar of Tarzoo, Sopore was tortured by CRPF on July 23, 2016, and died on July 31. The body of Aqib Ramzan of Lone Mohalla, Khonmoh was recovered on July 27, 2016 bearing marks of severe torture. Shabir Ahmad Mangoo of Khrew was beaten to death by armed forces on August 18, 2016, in front of his family members. Mansoor Ahmad Lone of Hardshiva, Sopore was tortured by personnel of the Army’s 22 RR regiment in their custody and died on September 14, 2016. A government employee, Abdul Qayoom Wangnoo of Aali Kadal, Srinagar was beaten severely by the CRPF personnel at Hyderpora, Srinagar on September 9, 2016, while he was on his way to work. He died in the hospital a few hours later. A teenager, Kaiser Amin Sofi was first tortured and then forced to consume poison by the police on October 10, 2016. He died in the hospital on November 4, 2016 after making a dying declaration.”

The report notes that “These cases are only recent evidence for the continuing phenomenon of the use of extreme torture by Indian State forces in Jammu and Kashmir. Torture has been long prevalent, and is most often considered a part of a continuum of coercive questioning and punishment. It includes both physical and psychological methods of infliction of pain, ranging from questioning, to verbal abuse, to ‘enhanced interrogation’ and other cruel and inhuman treatment that causes distress and disorientation, and outright physical torture which leads to injuries and may cause long term debilitation.”

The report establishes that “In Kashmir contemporary practices of torture and inhuman treatment, whether clandestine or public, must be understood within the context of an armed conflict….The collective punishment and torture of civilians and combatants often takes place during military-policing operations such as Cordon and Search Operations (CASOs) and Search and Destroy Operations (SADOs), enabled under extra-ordinary ‘disturbed areas’ and ‘special powers’ laws that allow the military and police to operate with impunity in civilian areas….These systemic practices and patterns are informed by long-standing historical connections between torture and colonial counter-insurgency warfare doctrine and strategy.”

These colonial legacies get a new lease of life in the context of the global ‘War On Terror’ narrative: “The post 9/11 world has seen a global resurgence in laws and discourse legitimising torture as a counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism tactic in liberal democracies.”

The report traces various phases and patterns in the use of torture by the Indian State: 1) Crackdowns and Mass Torture (1990-1992); 2) ‘Catch and Kill’ and the outsourcing of torture (1993-1996); 3) Civilian government and the normalisation of torture (1996— 2001); 4) ‘Healing Touch’ and the invisibilization of torture (2002-2008; and 5) Civilian uprisings, street protests and the re-visibilization of torture (2008—2018).

The report makes for difficult reading. It is clear from the report that torture in its various forms is not an exception in the Kashmir Valley - it is a daily reality, affecting even minor children. Torture is not necessarily inflicted to any specific purpose (such as procuring information) - it can be random. What, then, is the purpose of such random, widespread, routinised torture? The inescapable answer is: it is to subjugate a people, break their will, hold them against their will.

Reading the report, it is also clear that the torture cannot be blamed on a handful of “bad apples” - instances of ‘indiscipline’ in an otherwise disciplined armed force. The Indian armed forces are, indeed, highly disciplined - and the torture is likewise disciplined, performed with approval, protected with total impunity. Not a single accused person was prosecuted for human rights violations in Jammu and Kashmir.

The report documents 432 case studies of torture. Of these, in 326 cases, the victims were beaten; in 231, electrocuted; more than a hundred victims were stripped naked, put through roller treatment (using a heavy roller to apply pressure on the legs), restrained in stress positions, or hung upside down. Rape is a commonly used form of torture - both against men and women. Reading the use of “roller treatment”, it is impossible not to recall that this was the form of torture to which Rajan, the young engineering student of Calicut, was subjected to during the Emergency. Rajan was a victim of “disappearance” - and a symbol of what is often referred to as the “excesses of the Emergency.” This report reminds us that such torture is no thing of the past. It continues to be used all over India - and most of all, in Kashmir. In 252 cases, the victims were subjected to torture repeatedly.

Kashmir is one of the most densely militarised regions in the world: leading to a situation where civilians are in constant terror of arbitrary disappearance or torture. The report documents 144 military camps, 52 police stations and at least 15 joint interrogation centres which were sites of torture. The report “found that torture has been used in Kashmir by various Indian agencies (including armed forces) without any distinction of the political affiliation, gender or age. …that out of the total 432 cases, an inordinate 301 torture victims were civilians and 5 were ex-militants i.e., people who had already shunned militancy and had no involvement in any militant related activity when tortured. Of the 301 civilians, 20 were political activists associated with various organisations, 2 human rights activists, 3 journalists, 6 students and 12 were associated with Jamaat-e- Islami (a politico-religious group). 258 civilians did not have any affiliations with any organisations, political or otherwise.” Torture is then, a form of “collective punishment” inflicted on a whole people.

What about courts? Can victims not approach courts for justice? The report found that “In the early stages the judiciary was one institution of the State in which victims had faith, but this faith has also waned with the passage of time. Although supposed to be independent the judiciary has self-imposed limitations. There has been a lack of assertiveness on the part of the judges officiating in a conflict zone. Due to non- cooperation from the army and the police, the judiciary has been rendered ineffective. There are 4000 Contempt of Court petitions pending before the Srinagar bench of the High Court…This alarmingly high number highlights the total undermining of the judiciary in the state.”

The Jammu & Kashmir State Human Rights Commission exists - but in 2017, the government turned down almost 75% of the recommendations made by the Commission, accepting only 7 of the 44 recommendations made by it for compensation and ex gratis relief! The state government informed the Assembly in 2018 that out of the 229 recommendations made by the Commission since 2009, only 58 were accepted by the government!

The report makes a series of recommendations, listed below.

Recommendations To the International Community

- The UN Security Council should exercise its power to refer the situation in Jammu & Kashmir to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, under Article 13 (b) of the Rome Statute, acting under its obligations to maintain international peace and security.

- The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) should establish the Commission of Inquiry, as recommended in the report of Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), which should be mandated to investigate allegations of all human rights violations perpetrated in Jammu & Kashmir.

- Foreign governments and their embassies/missions in India should peruse this report for blacklisting personnel of various Indian armed forces formations mentioned in this report from obtaining visas. In case any of these alleged perpetrators are found to be present in a foreign territory, they should be prosecuted according to the principles of universal jurisdiction.

- UN-Department of Peacekeeping Operations (UN-DPKO) should peruse this report for blacklisting personnel of various Indian armed forces formations mentioned in this report and bar them from serving on UN-DPKO missions in any capacity. UN-DPKO should involve the civil society from Jammu Kashmir for vetting the applications of Indian armed forces before their deployment for international peacekeeping operations.

- The European Union (EU), which adopted a resolution on Kashmir on July 10, 2008 on allegations of mass graves in Kashmir, has been giving tariff benefits to India in direct contravention of its Generalized Scheme of Preference (GSP) trade policy, which is based on the foundation of protection and promotion of human rights. The EU, by continuing trade under GSP and allowing India to evade being part of the structured dialogue on human rights, becomes complicit. The EU should review its trade relations with India and withdraw GSP trade benefits to India.

- The European Parliament like it has in other contexts of institutionalised human rights abuses should adopt a resolution to demand the appointment of Commission of Inquiry by the UNHRC and also on its own institute a monitoring mechanism for monitoring human rights situation in Jammu & Kashmir through its diplomatic missions in New Delhi.

- International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC) should revise its Memorandum of Understanding with India and the government of India should allow the ICRC to work on its global mandate in Jammu & Kashmir.

- Under the provisions of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) doctrine, the international community should intervene diplomatically and force India to cease the ongoing human rights violations in Jammu & Kashmir and provide justice to the survivors of human rights abuses.

To the Government of India

- Give UN-OHCHR, all UN Special Rapporteurs and other Special Procedures, European Parliament and other International institutions unhindered access to Jammu & Kashmir to conduct impartial fact-finding into allegations of rights violations.

- Give global International human rights organisations unhindered access to Jammu & Kashmir to conduct impartial fact-finding into allegations of rights violations.

- Ensure that the material witnesses and individuals with knowledge of the occurrence of rights violations, including military, police, administrative officials and victims, receive protection against reprisals, threats and intimidation.

- Ensure that the material evidence in cases of torture by state armed forces be preserved.

- Ratify the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment (UNCAT), International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED) and Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

- Repeal all laws which are in contravention to the international human rights framework.

- Adopt rehabilitation policies in Jammu & Kashmir for the victims to overcome physical, psychological, economic and social consequences of torture.

To the International Civil Society

- Enhance their presence in Jammu & Kashmir and increase their activities regarding documenting and disseminating reports of the widespread human rights violations in the state.

- Facilitate a campaign to persuade UNHRC for appointing the Commission of Inquiry for investigation of the human rights violations in Jammu & Kashmir.

- Provide support, through their action, for the protection of the human rights defenders, lawyers and victims in Jammu & Kashmir.

- India, which is seeking a permanent seat in the UN Security Council, should be held morally accountable for violations of human rights in Jammu & Kashmir.

This report should be widely read and discussed among Indian citizens, trade unions, and people’s movements of all kinds, who should raise and amplify the recommendations made by the report. It is a call to the conscience of every Indian.

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

-

2011-2020

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

-

2019

- JANUARY-2019

- FEBRUARY-2019

- MARCH-2019

- APRIL-2019

- May-2019

-

LIBERATION, JUNE 2019

- Lok Sabha Results 2019: Summon Up All Strength for Tough Challenges Ahead

- The Politics Behind Demolition of Vidyasagar's Statue And BJP's Mission Bengal 2019

- RSS and BJP Cannot Deny Their Affinity With Hindutva Terrorist Godse

- Two Women, Two Cops - A Study In Terror, Privilege And Prejudice

- What We Can Learn From Modi's Scripted 'Interviews'

- Mass Retrenchments in IT Sector

- Institutionalised Brutality: Torture in Jammu and Kashmir

- Harassment and Human Rights Violations

- Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism is Changing India

- IIMS Study Camp in Mysore on Ambedkar's Writings

- CPI Leader Fago Tanti Killed By BJP-Backed Criminals in Begusarai

- May Day 2019 in Karnataka

- Comrade Amar Lohar!

- Comrade Karamchand Mahto

- Did IAF Suppress This Fact Till Polling To Avoid Embarrassing Modi Government?

- Fascism: I sometimes fear...

- Liberation JULY 2019

- LIBERATION, August 2019

- Liberation, SEPTEMBER 2019

- Liberation, OCTOBER 2019

- Liberation, NOVEMBER 2019

- Liberation, DECEMBER 2019

- 2020

- 2021-2030

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org