(This is an abridged version of a piece that appeared in scroll.in on 23 July 2017)

A Mumbai-based media company Culture Machine announced a new policy of offering women leave on the first day of their period – and this has set off a storm of debate, polarizing opinions of women themselves.

Several women I know have admitted to feeling “confused” on this debate. Should they stop keeping quiet about periods and start demanding that the pain and discomfort they feel during periods be acknowledged as normal and deserving of rest and relief? Or will doing so give a new lease of life to the demons of discrimination – that women have defeated with such effort – that claim women are “lesser than” men because always handicapped by their bodies?

Is there a way out of this double-bind?

Women In Bihar Won Period Leave In 1992

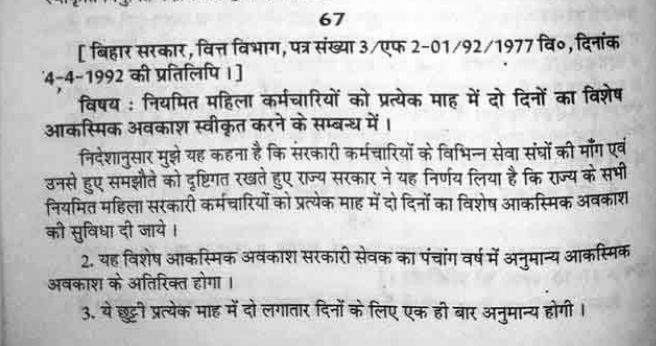

Did you think the Mumbai company Culture Machine’s policy of period leave is an outlandish idea, unlikely to work in India? Well, you might be surprised, then, to know that women employees in Bihar Government services have been able to avail of two days of leave every month, ever since 1992. The Human Resource guidelines of the Bihar Government http://brlp.in/documents/11369/15834/HR+Manual.pdf/a3157cfe-dc8f-4ae0-bd7e-3b0965b45ae2 state:

‘All women staff is eligible to avail two days of special leave every month because of biological reason (sic). This is in addition to all the other eligible leaves.’

The Government Order dated 2.01.1992 states that in keeping with the demand raised by various employees associations and the agreement arrived at with them, the state government orders that all women who are regular government employees will be given two days of special casual leave. The order clarifies that ‘two days’ refers to two consecutive days every month.

I spoke to Comrade Rambali Prasad, General Secretary of the Bihar State Non-Gazetted Employees’ Federation’s (Gope faction), closely associated with the AICCTU, for the story behind this policy. He told me, “Several of us toured various Bihar districts in 1990, meeting with groups of employees. Women employees everywhere raised the need for leave in keeping with their monthly cycle. Our Federation included it as one of the key demands of an employees’ strike in 1990. Negotiations with the union leaders took place with the then Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav, who to his credit agreed without any hesitation that this demand had merit. That’s how the order was passed. And today, employees’ struggles have resulted in this order being extended to contract employees (such as teachers) as well.”

At my request, Shashi Yadav, General Secretary of AIPWA in Bihar, spoke to women employees in several districts of Bihar, to ask them if they experienced any problems in availing of this leave. All the women she spoke to affirmed that women employees routinely availed of this leave without any problems. The leave is available for women until the age of 45, but women reported that they are easily able to get an extension and avail of it till the onset of menopause, at whatever age that may be in their individual case. Did period leave become an occasion for sexist comments and speculation by male colleagues, Shashi asked them. One woman replied, “Those who make sexist comments or indulge in harassment need no excuse to do so,” and another said “Some men make sexist remarks even when we wear a nice sari, but that does not mean we stop wearing nice saris.”

Bihar Government employees said that each woman decides when she needs the two days leave most – some avail of it on the first two days of the period, others on the last two days preceding the onset of the period, and they are answerable to no one about when they choose to avail of it. In other words, period leave is tied to each individual woman’s experience of her period, rather than being medicalized and resulting in needless scrutiny and violation of privacy to justify the leave.

Do All Women Need Period Leave?

Periods need not be debilitating to justify Period Leave. Sharanya Gopinathan http://theladiesfinger.com/period-leave/ points out that it is not that women can’t work in spite of periods, but that they should not have to. The 8-hour working day or the weekend or maternity leave – all labour rights that we take more or less for granted today – were won by workers’ movements in the face of arguments by employers that these would affect productivity and the economy. Even today, women workers who demand implementation of maternity leave and other entitlements are often laid off by employers; does that delegitimize the concept of maternity leave?

Periods need not be debilitating to justify Period Leave. Sharanya Gopinathan http://theladiesfinger.com/period-leave/ points out that it is not that women can’t work in spite of periods, but that they should not have to. The 8-hour working day or the weekend or maternity leave – all labour rights that we take more or less for granted today – were won by workers’ movements in the face of arguments by employers that these would affect productivity and the economy. Even today, women workers who demand implementation of maternity leave and other entitlements are often laid off by employers; does that delegitimize the concept of maternity leave?

The point here is that the “average” worker is not male (40 % of the world’s workforce is female http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.FE.ZS). This means that the workplace, too, cannot be gender-blind. Having periods does not necessarily mean ‘tabiyat kharab hai’; menstruation is not a malfunction or a handicap or a disease; it is normal and natural for most women. Instead of women having to ‘adjust’ to fit workplaces designed for men, workplaces need to be adjusted and transformed to fit women. (And the same goes for the differently-abled persons).

Do Women Need To Change? Or Does 'Work' Need To Change?

The Hindi saying goes ‘Naach na aaye aangan tedha’: if you don’t know how to dance don’t accuse the yard of being skewed. Are complaints about periods and demands for Period Leave basically an excuse made by women who can’t hold their own in a competitive labour market? Or should we perhaps begin to recognize that women do not keep having to prove their competence and their excellence at the expense of their own health and well-being: it is the aangan – our society and workplaces – that is indeed skewed and needs changing so that women can dance better.

Feminist anthropologist Emily Martin (The Woman in the Body: A Cultural Analysis of Reproduction, Beacon Press, 1987) argues that in industrialized capitalist societies, “Women are perceived as malfunctioning and their hormones out of balance rather than the organization of society and work perceived as in need of a transformation to demand less constant discipline and productivity.” The way out of the bind we discussed above, Martin suggests, is “to focus on women’s experiential statements that they function differently during certain days, in ways that make it harder for them to tolerate the discipline required by work in our society. We could then perhaps hear these statements not as warnings of the flaws inside women that need to be fixed but as insights into flaws in society that need to be addressed.”

And what about the eternal menstrual and premenstrual bugbear: anger? Martin suggests that society – and science too – tends to see anger as natural in men, but a sign of irrationality and a source of instability in women. The lowered controls in premenstrual or menopausal periods allow women to express a perfectly valid and justified anger that they are socially trained to suppress at other times. Martin writes, “To see anger as a blessing instead of as an illness, it may be necessary for women to feel that their rage is legitimate. To feel that their rage is legitimate, it may be necessary for women to understand their structural position in society, and this in turn may entail consciousness of themselves as members of a group that is denied full membership in society simply on the basis of gender.”

Would Period Leave Trigger Discrimination At Work?

Could Period Leave lead to violations of women’s rights at work? Of course, it could – absolutely anything can be a pretext for patriarchal oppression and violence at work. A 2002 study of Nike and Adidas workers in Indonesia factories (We Are Not Machines, Timothy Connor https://cleanclothes.org/resources/publications/we-are-not-machines.pdf) found that in the Nikomas Gemilang factory, workers wanting to claim legally-mandated menstrual leave had to “go through the humiliating process of proving they are menstruating by pulling down their pants in front of female factory doctors.” But such violence does not need Period Leave as a trigger: after all, women workers in a Kerala factory in 2014 were strip-searched https://scroll.in/article/698178/kerala-activists-fight-menstrual-taboos-by-mailing-napkins-to-factory-where-women-were-strip-searched by female supervisors to find out who left a used sanitary pad in the bathroom.

As things stand, there are dozens of discriminatory work conditions, rules, and restrictions that are uniquely applied to women at workplaces in globalizing India. Many women workers in India do not even have access to toilets. Women in Tamil Nadu garment factories are prevented from using mobile phones and speaking to co-workers, and are kept confined to factory and hostel premises http://www.thenewsminute.com/lives/623. A report (http://sanhati.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Production_of_Torture.pdf) by civil liberties and feminist organizations found that women garment workers in Karnataka are subjected to similar restrictions and intrusive surveillance, including sending someone to follow women workers into toilets to make sure they do not “waste time.” This report found that “male supervisors, floor in-charges, including managers, call the women workers by abusive names…and cast aspersions on their character.”

We need to reject and challenge these discriminatory forms of workplace discipline that subject women to hostile and violent work conditions that take away their autonomy. At the same time, we need to demand that workplace policies be tailored to ensure the privacy, dignity, and physical and mental well-being of all workers, acknowledging that this can call for distinct and unique policies for women.

If Men Could Menstruate

In her classic article ‘If Men Could Menstruate’ http://www.mylittleredbook.net/imcm_orig.pdf, feminist Gloria Steinem had suggested that women were not “lesser than” men because of menstruation; instead menstruation itself is seen negatively because it is experienced by women in a patriarchal society. Adding to Steinem’s picture of what the world would do differently if men (and not women) could menstruate, Martin writes: “we would all be expected to alter our activities monthly as well as daily and weekly and enter a time and space organized to maximize the special powers released around the time of menstruation while minimizing the discomforts.”

Surely we do not need men to experience menstruation in order for us to see that our lives (whether related to domestic labour or to waged work) could and should be organized so that women can experience minimum discomfort and be able to avail to the maximum of the capacities unleashed around and during menstruation? Period Leave is a step in the direction of such a world.

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

-

2011-2020

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

-

2017

- January-2017

- February-2017

- March-2017

- April-2017

- May-2017

- June-2017

- July-2017

-

August-2017

- The Call of August 15, 2017: Resist the Dictatorial Design of Modi Raj

- Mandsaur To Jantar Mantar: Kisan Mukti Yatra

- Wave of Protests Against Spate of Communal Mob Lynchings

- Reading Ambedkar in Modi's India

- Adani SLAPP Costs EPW Editor His Job

- Amarnath Killings: Rebuff Communal And Divisive Propaganda

- Basirhat Riots: Reject Hate, Strengthen Harmony

- GST: Another Recipe For Increased Inequality And Deeper Economic Crisis

- Modi's Israel Visit: A Betrayal of Democratic Principles

- The Period Leave Debate: Women Can Dance Fine, It's The Yard That Is Skewed And Needs Correction

- Three Months of BJP Government in Uttarakhand

- Two Mahadalits Convicted Under Draconian Prohibition Law In Bihar

- Attack by BJP-Supported Goons on AIPWA and CPI(ML) Leader Comrade Jeera Bharti

- Domestic Workers Protest in NOIDA, Face Repression, Eviction from Homes and Jobs

- 'Azaadi Kooch' Marks One Year of Una Resistance To Gau-Goons

- September-2017

- October-2017

- November-2017

- December-2017

- 2018

- 2019

- 2020

- 2021-2030

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org