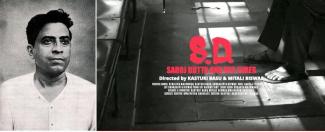

Directors : Kasturi Basu and Mitali Biswas

115 mins / 2018 / India / Bengali, English with English Subtitles.

One of the many Kolkata educated women who went to work in the villages during the Tebhaga movement, was Bela Dutta, Saroj Dutta’s wife. In the film, SD and his Times, the nonagenarian speaks along with her son to the film makers. Her memory and wit both sharp. In the early 1940s she recollects, that her husband Saroj Dutta, had come to leave her at the railway station as she went off to the rural front to fight alongside peasants. She joins the historic struggle against a brutal state that was backing the landlords and pushing hunger. Later on she disapprovingly narrates how the leadership flounders as peasant initiative rises, and asks the fierce women revolutionaries, to “go back to the kitchen”. She breaks gender scripts and six decades after the Tebhaga movement, Bela Dutta is still shocked and disdainful of the command for backing off. She narrates how Saroj Dutta, who became active in the communist movement much after her, enquires from her upon her return on why she had retreated. It however clearly emerges in the course of the film that the couple never retreated. They immerse themselves instead, into the communist movement. Each doing what they can as per the call of the time. They proceed without regret, firm only in their commitment, be it when she has to sell her jewellery for buying a printing press for the party or his getting thrown out of a job for standing up for workers’s rights and refusing to call freedom fighters dacoits. The film takes us through Saroj Dutta’s involvement as he immerses himself in chronicling the revolutionary movement and the country progresses from Tebhaga to Telengana and to the Naxalbari movement; the formation of CPI ML; through the failure of Indian state towards its peasants; and eventually to SD’s time in jail, arrest and custodial killing. The film true to its title locates Comrade Saroj Dutta within the movements that defined his life and his death.

The story that goes into the making of history by ordinary oppressed people is by no means an ordinary one. Yet it is revealing that stories of those like SD and others who erased themselves both in their own poems, and in their revolutionary work through nom de guerre, fiercely lit up political discourses for transformation. When it came to giving up their lives, they did not flinch. The film begins with a pensive realization by the revolutionary of his imminent death.

The film by Kasturi Basu and Mitali Biswas is, as disclosed at the end, a cathartic retelling of the stories that they grew up hearing. It hence looks back at the brutalities unleashed on those who sought a just society. Saroj Dutta has been declared ‘missing’ since 5 August 1971, but it is a certainty that he was killed in police custody in an open park. A year later Charu Mazumdar was tortured and killed in 1972 in Lal Bazar police station. In the 1960s and ’70s of Kolkata hundreds of youth were killed by Indian National Congress goons and state forces for dissenting. The city carried heavily in its heart many of these stories, occasionally someone coming out with literary work and non-fiction pieces. But more or less it has been undocumented on film. The inadequacy of the telling of these stories also denied justice to those who were killed and declared, ‘disappeared’ or ‘missing’. The files of the killings have remained closed and attempts at reopening them have met with a cold refusal by the courts. The film highlights how the project of democracy in India has been incomplete and how state institutions failed its people. There are rare on camera testimonies by those who lived in the period, including Professor Debiprasad Chattopadhyay and his wife from whose home SD was arrested and taken away before being killed, and others like Comrade Nemai Ghosh who spent long years in jail as a political prisoner during the Emergency. There are archival footage of several interviews done by Comrade Abhijit Majumdar of communist revolutionaries from Naxalbari.

The film is beautifully woven together with music. Tebhaga, Telengana, Naxalbari breaking out on film through songs of resistance. The film also traces the formations of the communist parties, from CPI, to CPI-M and CPI-ML and the debates that led to them. The 1960s are placed within the context of Vietnam, Congo and Patrice Lumumba, Paris student movement of 1968. The simmering anger cut across the world and youth were taking history by the horns. Saroj Dutta spoke straight to the youth. His life comes across in interviews of people who knew him, and through enactment of episodes from his life. The enactments often giving clues to what becomes clearer later in interviews. Small details like these make the film engaging. The sound communicating both the distant past as well as the urgency of the present.

The ideas that lit flames of struggle during Comrade Saroj Dutta’s times are captured eloquently by the film makers. His writing were varied and sharp but his focus was clear.

The writings and poetry bringing forth the urgency of rebelling. Even as he chronicled and commented, Comrade Dutta dissected mainstream journalism by pointing out the façade and charades, mocking at bourgeois values and social order that mainstream media sought to protect. People were moved by what he wrote and his pen became his weapon. The threat of the pen was so large that he was eventually killed in custody.

Naxalbari movement gave power to the peasants and adivasis to take charge of their own future in post independent India. It was the only way they could put an end to brutal exploitation wherein they surrendered everything they grew to landlords to pay the rent as sharecroppers. Archival footage trace and establish this in the film. That the peasant resistance in a small region of Siliguri, Bengal could engulf the country and capture the imagination of youth indicates the anger and discontent. In an interesting footage, it is shown how immediately after Naxalbari happened, there were nearly no political forces willing to speak for the landlords and their exploitative systems. Even then, however, the national media, glossed over the structural inequities. The film highlights through Saroj Dutta’s journalistic column under the name of Shashank, how newspapers were silent about the peasants’ condition and subsequent rebellion, and how they deliberately sought to present the militant resistance as a law and order problem, misleading and misrepresenting the reality from larger public. The party organ and journalistic work of comrades then became the vehicle for news on rural reality. Its popularity reflected in the wide readership even in urban areas.

Several ideas and icons got challenged as young people entered the movement in the 1960s. The culture of fierce debates re-entered public discourses. One of it was to do with the statues that were in public spaces as heroes of people and attacks on them. Currently when statue building has reached a new peak in India, the raising of this question within the film triggers several thoughts. The film refers to several letters that were part of inner party debates and discussions. Saroj Dutta’s response shows that he understood youth, their iconoclasm, energy and anger even though his focus was on peasant resistance.

If we look at the books and films on contemporary Indian history, there is almost a denial of the crisis faced by Indian democracy in the 1960s that eventually spelt out as Naxalbari. Credit goes to the film makers and their team for telling this part of people’s history. They also bring out Saroj Dutta’s life, poetry and writings evocatively both in sound and image. No doubt, many more such films need to be made for telling history as well as for preserving memory of struggles. Currently when the term urban naxal has gained ground and is being adopted by a wide section of people indicating their dissent against government’s policies, it is interesting to see a film that allows a peek into the history of the term. Through Saroj Dutta and his times, we also get to think on troubling developments of our times: be it dispossession of the peasants, the denial of rights and justice, fake encounters or revivalist statue building. While many got martyred and killed, the questions that the revolutionaries raised at that time, did not quite die and in those memories there are new tools to think.

Liberation Archive

- 2001-2010

-

2011-2020

- 2011

- 2012

- 2013

- 2014

- 2015

- 2016

- 2017

- 2018

-

2019

- JANUARY-2019

-

FEBRUARY-2019

- Republic Day 2019: Rescue India from the Modi Disaster Rebuild Indian Democracy

- 10% EBC Reservation: Expose and Rebuff the Modi Government's Desperate Deflection Tactics

- New Year Begins With New Hope

- Citizenship and Sedition: BJP's Communal And Repressive Agenda

- All India Workers' Strike 2019

- Repression Unleashed On Daikin Workers

- Indefinite Strike by Mid-Day Meal Cooks in Bihar

- The Bhojpur Revolutionaries Fought For Freedom, Equality, Justice And Unity

- 15th Martyrdom Day of Mahendra Singh : Rally Pledges to Defeat BJP, Hoist Red Flag Over Bagodar

- Socialism 2018: People's Need Not Corporate Greed

- A Conversation With A Young MP From Spain's Podemos

- Somyot's Story Affirms The Importance of International Solidarity

- With Trumpets Blazing : Martyrdom Centenary of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht

- SD: Saroj Dutta and his Times

- Mrinal Sen (1923-2018)

- "Universal Basic Income" : The Next 'Jumla'?

- MARCH-2019

- APRIL-2019

- May-2019

- LIBERATION, JUNE 2019

- Liberation JULY 2019

- LIBERATION, August 2019

- Liberation, SEPTEMBER 2019

- Liberation, OCTOBER 2019

- Liberation, NOVEMBER 2019

- Liberation, DECEMBER 2019

- 2020

- 2021-2030

Charu Bhawan, U-90, Shakarpur, Delhi 110092

Phone: +91-11-42785864 | Fax:+91-11-42785864 | +91 9717274961

E-mail: info@cpiml.org